Old Woman saying Grace, known as ‘The Prayer without End’, Nicolaes Maes, c. 1656

Religious principles are a frequent theme in didactic literature of the long nineteenth century. Religion was vitally important to women and was often used in arguments to improve their position in their family and society.

It gave women a voice and was significantly valued by the women themselves – as religion formed their identities, as mothers, wives, and their relationship to their communities. For many women of this period, the Christian God of the Bible was a pre-eminent force in their lives, directing them by his providence and preparing them for an eternal future with him and other believers in an eternal home. Love and service for God – in whatever manifestation that presented – was supreme.

This three-part blog series will demonstrate the importance of understanding the religiosity of women in this period, highlighting how religion shaped identities, helps us understand debates over women’s position in society, reveals agency, offers opportunities and catalyses activism. This first post will focus on religion and identity.

While it would be remiss to suggest that all women in the long nineteenth century were religious (they weren’t), those who were eminently religious did not consider it a tangential part of their lives; religion was the axiom which underlay their other activities; whether political, family-orientated, or career-driven – religious experience was central.

The importance of faith is especially evident in diaries and letters of nonconformist women (Baptists, Quakers, Unitarians and Congregationalists) which I have examined from 1780-1850. Anna Braithewaite, a Quaker minister in the early nineteenth century, comments in a letter (in July 1823) to her husband how greatly she missed him and her children – and yet considered her love and service to God as the greatest priority:

“My mind was brought to a close sense of the separation between me and all who are dear to me… I felt to the full the reality and bitterness of the sacrifice, yet I desired to be preserved in a cheerful surrender of my all unto Him whom I love, and whom I feel utterly unworthy to serve.”

Another Quaker woman, Elizabeth J.J. Robson, noted that the greatest happiness could only be found in Christian religion, in her diary in 1844:

“I have thought that we cannot be perfectly happy, unless we be true Christians, self-denying, cross-bearing Christians.”

Jane Attwater, a pious Baptist lady, frequently wrote prayers in her diaries. In March 1782, she praised God for his goodness, and chided herself for being less than fully devoted to Him:

“How little alas can I do for such infinite goodness, o for a heart intirely devoted to thy service.”

Many women believed that they ought to love God, in light of all that he had done for them, and that this ought to manifest in obedience to his calling upon their life. Religion was not a peripheral part of life for these pious women – it was the centrepiece.

Faith provided happiness and purpose. Whether women found themselves committed mainly to domestic work, or active in the ‘public sphere’, religious women believed their lives were to be both directed by and towards God. Identity was found in their love and service to God, who was pre-eminent in their lives.

Angela Platt is a PhD student in Royal Holloway’s Department of History. Her thesis explores the lives of nonconformist families in England between 1780 and 1850. The next post will explore how concepts of ‘separate spheres’ and agency can be better understood through religion.

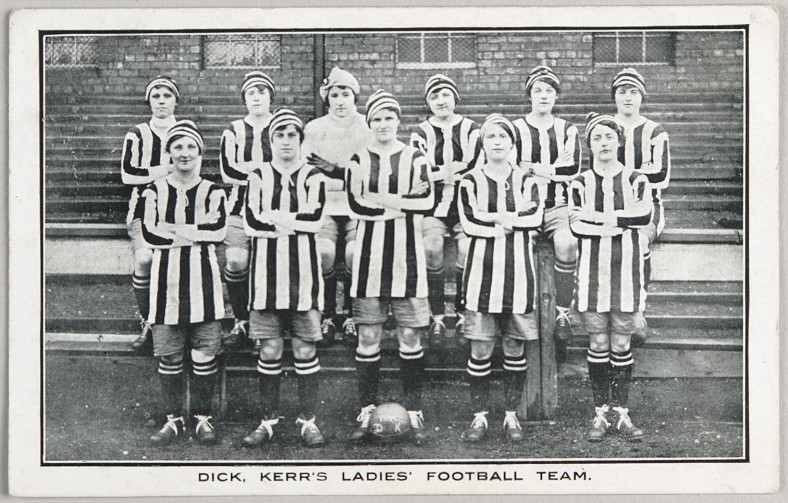

These women really were trailblazers, and yet our foremothers and their path-breaking achievements are nearly forgotten.

These women really were trailblazers, and yet our foremothers and their path-breaking achievements are nearly forgotten.

History was made in 2018 when

History was made in 2018 when